Darius and I are nothing alike, and yet it feels as though writer Adib Khorram expresses many of my past and present struggles through him. From my life with depression with a desperation to be understood and feel connected, and as a Portlander myself, Khorram has walked me through my mind and my heart with intelligence, charm and wit and I wanted to burst into tears at the end. Darius’ struggles with his body image, his depression, family and heritage all resonate with me, despite my much greater age than his. His internal monologue is note perfect, making his depression deeply relatable with, empowering readers living with depression and clarifying it for those who don’t understand it. This isn’t a tidy story, nothing gets overcome, but with great integrity the author shows that those of us living with mental health difficulties can live perfectly happy, connected and loved lives.

With that in mind, ‘your place was empty’ is a saying that comes up again and again. It’s an idea that the Farsi language expresses in ways English can’t – a metaphor for a seat that’s held empty for someone who is supposed to be there, whether they know it or not. The idea at its heart about human connection opens avenues for belonging that Darius doesn’t anticipate. He develops a sudden best friendship with boy-next-door Sohrab, but also watches his otherwise aloof father connect with Darius’ Iranian family in ways he didn’t think him capable of. Stereotypical American individualism is shown to be unnecessary in Iran and it’s not just Darius who grows because of it.

It’s this element of Darius the Great is Not Okay that I loved most of all – that the characters who start the book ‘stuck’ are freed up through having had their lives seen and reflected back through a different cultural prism than they’re used to. It’s overly simplistic perhaps, but it’s still a well considered celebration of diversity, and again note perfect in showing not just Darius and and his Dad other avenues they can explore just for being, but people they come in contact with too (particularly one of Darius’ bullies). It’s Darius’ and Stephen’s dualities that make them genuinely interesting and likeable, and we’re reminded that more Soulless Minions of Orthodoxy than we might expect look at unapologetic, authentic, multifaceted and yes flawed people with more envy than we realise.

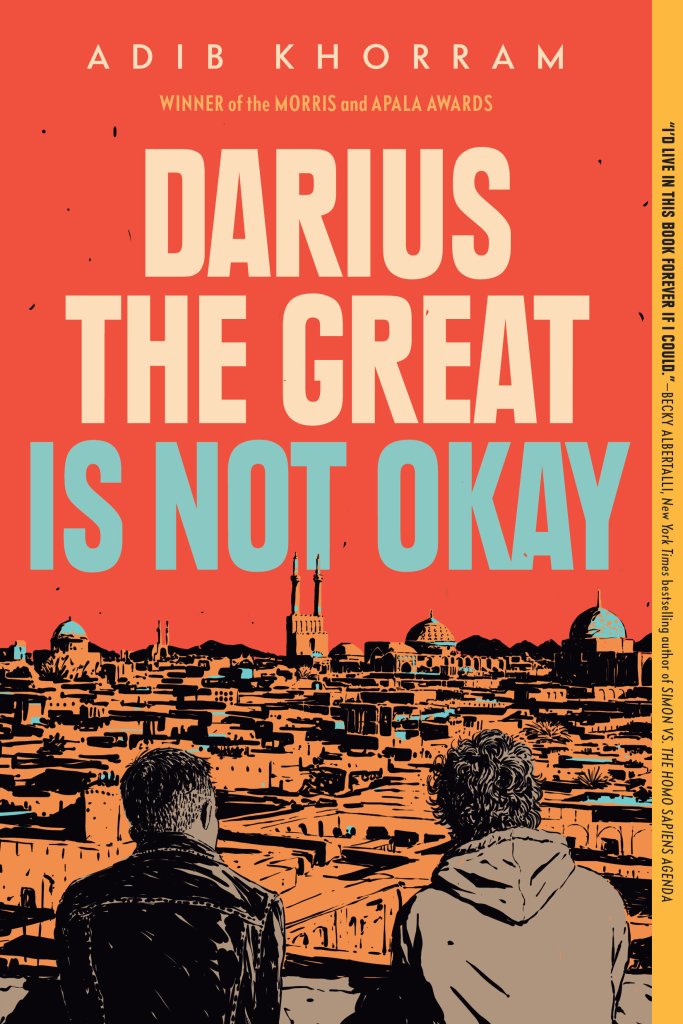

The book doesn’t tie any of its issues or relationships up with a bow, indeed when the family leaves Iran, Darius and his mother acknowledge they’ll never see his Babou again (and Sohrab faces far worse). But it’s not sappy either, and I was continually surprised by how charmed I was by the depiction of Yazd, its architecture and its food. The love the author has for the rituals around tea, as well as the country’s architecture and history flies off the page, and I was relieved that Darius’ friendship with Sohrab was on the one hand not romantic, on the other not overly idealised. It’s a coming of age tale where the protagonist starts understanding there are ways of living well with depression, but it’s also a story about hope and shared humanity (the repeated references to Star Trek: TNG are not coincidental). It’s quite possibly the loveliest book I’ve ever read.